We live in a stereotyped society; a society that promotes you to be ‘different', as long as you go along with the public opinion. What is ‘public opinion' and why do we need to follow it all the time? I had read somewhere in a Greek philosophy book about the ‘tyranny of the majority' and I found it totally correct. We say in many cases, the majority ‘wins', but what about that certain minority's opinion? Where does it go? Humans are introduced to the stereotypes of society; from the day they are born. They accept them at early age and then consequently are addicted to them. Later on they enter a comfort zone, where all is settled. All is well. Most of the times they are not even themselves, because they have got to be that type of person that is conformed to all rules of society. You begin your school life. Lack of originality… At school you have to be the student who is responsible and disciplined. You start learning all the cliché phrases… “The tomatoes are ripe The sea is turbulent The truth is hard Respect is gained Justice is blind” If you start writing essays which express extreme way of thinking or do not conform to the general opinion, you are marginalized. There goes your freedom of expression. Follow the rules. People love stereotypes. They know they are easier to handle. No need to search for something more. Once a woman says ‘I don't want to be a housewife, she will face discountenance. Who said you have to be one? Who ordered this definition of your identity? Why do we follow society's norms? There is no stereotype. You were born free to be whoever you were intended to be. You are born to be original. Maybe you were intended to be: Wild as the wind in a desert Free as a spirit An idea A concept An illusion Or a Bird who flies to the unknown skies A hobo soul A traveler that needs no compass You do not fit into other people's molds Birds don't care about stereotypes Show me your arguments for a stereotypical life.

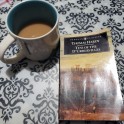

Despite the fact that staying at home under self-isolation was supposed to be boring, restrictive, and repetitive, I find myself to be quite comforted by the routine life that I seem to be leading. Waking up every morning knowing that there won't be any new or foreign event interrupting my peaceful to-do list was a comfort I never knew I needed. The constant speed at which life revolved was halted by a microscopic particle and within one night, everything that our daily routine was composed of was shut down. Along with the lack of external daily routine, so went our daily sources of anxiety. Gone were the creeping sense of anxiety that came with deadlines and due dates, replaced by sourdough baking, DIY projects, and personal reflection. Repetition was no longer a dreadful weight to bear, but a comforting weighted blanket that calmed down the waves of anxiety from the unknown. Every morning, I woke up with the comfort of routine in my mind. It was a blessing despite the havoc wreaked by COVID-19, because even if situations around the world continued to change and evolve, there was peace within the motions I went through everyday. The actions I took in a hurry were now done with the utmost pride and care, whether it be brewing a cup of coffee in the morning or reading a tattered copy of a well read "Tess of the d'Urberville". Such consciousness of one's action can only be found within routine, I supposed. The story of Tess and her discourses remained the same, yet I was not. Gone were the person who read Tess' story as a precursor for a class essay, replaced by this person who knew that there was no purpose to reading the book again, other than well, reading the book again. To those who found the act of reading the same text over and over with no particular goal in mind lacked logic, I had to agree, it really did not. There was no logical reason for a person to be reading the same story again and again, but I argue that the person who read the story was the point. The person who read "Tess of the d'Urberville" once was not the person who read it thrice, and thus the point of re-reading. Had it not been for the slowed down pace of life amidst the pandemic, I would never have came to the reason why I kept coming back to the same books and stories I read countless times in the past, all thanks to the routine life I lead and the comfort I found within it. Time was no longer measured by hours, minutes, and seconds, but by case numbers, news predictions, and death tolls. The very same building block that once ruled our lives lost its reign, and for the first time in our conscious history, we got the power to decide, in the relative comfort of our routine, what we get to make of life and ourselves. For the time being, mine will be the different selves I possess as I read "Tess of the d'Urberville" for the nth time. What will be yours?

We've all heard it. We've all felt it. Someone falls victim to suicide and the *nearly* unanimous cry is, “Why didn't they get help?!” “Why didn't they tell someone?!” Chances are really good that they tried. They tried really hard. But most people who are not at risk of suicide think that the path to it is paved with bright neon signs that say, “SUICIDE! THIS WAY!” The fact is that no matter what side of the political and religious spectrums you are, most people recoil from the subject of death, and the very idea that someone could intentionally end their own life goes against every fiber of our being. So, unless we are forced to deal with the ugly aftermath, we downplay it as much as possible, assuring ourselves that if we saw someone on that awful road, we would recognize it. But would we really? And do we really think that someone who is contemplating suicide sits there logically weighing the pros and cons before seeking advice from their friends and family? Yeah, I didn't think so. In order to recognize the real signs, we first need to get it out of our head that self-inflicted injury or death is about death. It's about pain. Think about the last time you got the norovirus or food poisoning. You felt horrible. It goes on and on and you just want it to stop. Your body contorts involuntarily. You can't think about anything else except that you just. Want. It. To. Stop. What if, instead of twenty-four hours, this state of being kept going – indefinitely. Now, let's imagine that, inexplicably, no one can tell that you have food poisoning. They walk by, try to have conversations with you, go about their business – all while you're being actively, violently ill. You can't speak except in single words and basic concepts. Some of the people who pass by are annoyed. They can't see what your feeling and they wonder why you won't speak in full sentences or aren't paying attention to what they were saying. Others think maybe something's wrong with you and that makes them uncomfortable, so they hurry by. Still others want to help, but they also kind of think – deep down – that you're being a big baby. “Chin up!” they say. “Everything's going to be ok! There was this time when I didn't feel good, so I started exercising and that helped so much! You should try it!” Meanwhile the life is draining out of you and you care less and less. You start to feel as numb as a rock. You may as well be one. A rock can't feel. The more pain you're in and the longer it lasts, the more you become singularly focused on just making it stop. It doesn't matter how. In your helpless state, what you need is someone to recognize that your silence is pain, that your cries are not dramatic, that you are not weak or without faith. You need someone to get down on the bathroom floor and hold your hair back. Because ultimately, it's little, real, meaningful gestures that can help guide hurting people off a path they don't even realize they are on. What signs do we need to be watching for? Everyone is different, so everyone is going to behave differently when they are struggling. Be vigilant when someone is not acting like themselves. They don't seem to be enjoying the things they usually enjoy. Smiles may be scarce and forced. They stay in bed or lay in bed for unusual lengths of times (don't we all want to curl up in bed when we aren't feeling well?). If they go as far as to communicate with us, we need to listen carefully. Don't dismiss self-deprecating language, even if it sounds like a joke. Know when to encourage socialization and when to recognize that it's too much. Recognize also that your own scope of aid may not be enough. Your friend may need gentle nudges towards getting professional help. And if we hear about someone who has fallen victim to suicide – let's not dead-shame. Instead, lets redouble our efforts and pay close attention to the hurting people in our lives. Let empathy wash away the fear and discomfort that so many of us have in the presence of pain. Embody comfort. Listen. Be there. Love.