I love the water. I could easily trace the origin of this passion back to the eleven years I spent as a competitive swimmer. Even now, years after retiring from the sport, I find myself returning to the water whenever I need a calm place to contemplate the world and my place within it. I'm thankful for this reconciliation, given that my relationship with the water during the swimming years had more of a love-hate nature to it. As a ten-year-old, I didn't know how to handle my excitement. I absolutely adored swimming, making so many friends and seeing tangible signs of success. My heartbeat rang in my ears every time I stepped onto that starting block, and oh, what a rush it gave me. Every time I blasted into the water, it seemed as though I'd shave ten, maybe even twenty seconds off of my previous best time. I even lost count of my laps in one of those races, but it didn't seem to impact the final result all that much. I couldn't get enough swimming in my life. But this pattern couldn't continue forever. In my teenage years of racing, I encountered numerous obstacles I hadn't previously faced. On one occasion, my goggles completely filled up with water. Unable to see, I had such a horrendous result that I actively avoided talking to my coach. In another instance, I hyperventilated in the middle of the race, having to stop early and getting disqualified as a result. Those examples don't even account for the races where I felt ready to go, only to simply come up on the losing end. I had no excuse; I just fell short of expectations. As the years progressed, the failures piled up while the successes seemingly hit a wall. Discouraged and devastated, I had many a breakdown on my bedroom floor. “What was it all for?” “Was I always destined to crash and burn?” “Did any of this even matter?” I grew so frustrated with all of those early mornings and endless laps not seeming to matter when the chips were down. I abandoned the pool, festering with resentment for the sport that had seemingly betrayed me. Then, I was confronted by a more challenging question: “Who are you, if not a swimmer?” I hadn't had to face this question in a number of years. I was the swimmer; that's all there was to it. My identity was wrapped up in being an athlete. I took great pride in it because it took all of my effort to maintain that status. But now that I had removed this label, I didn't know who I was anymore. My short-sighted beliefs became apparent to me when I took part in a 24-hour sporting marathon. I was destroyed. Physically, mentally, emotionally, spiritually, the whole nine. I was spent. There was NO way I could have the audacity to think I was an athlete after that, when all of my capabilities were stripped away from me. Only by the grace of God did I make it through that marathon, because I had no strength of my own to rely on. However, it was through brokenness and dependency that actually gave me freedom to embrace the future ahead of me. Since my identity was no longer wrapped up in being a swimmer, races didn't have the same hold over me. My worth was no longer determined by the time on the clock. I could swim because I wanted to swim, and I could take pride in putting my best effort forward every time I touched the water. I could race with an attitude of gratitude, being thankful for the opportunities I had to compete against formidable individuals. I ended up returning to competitive swimming for one more year, but honestly, I didn't see any huge improvements in my results. Yet, the shift that transpired during my pause from the sport influenced my whole outlook on life. Swimming taught me that, if I wanted to stay in the water, I needed to embrace the waves. It's an inevitable part of the sport; still water might be a safe place, but it's also a sign of stagnancy. There would be peaks where I felt like I could soar, but there would also be dips where my confidence sank to the bottom of the pool. The key would be to keep steady in the midst of the waves in all of their ferocious power. I learned that it was okay to acknowledge when they've rocked me, but I must remember that my identity isn't defined by my ebbs and flows. I'm a child of an eternal God who far surpasses my immediate circumstances, and in Him can I anchor my true worth. This has been a crucial revelation that I've carried with me into the writing world, particularly in the midst of COVID-19. I can't count the number of times I've heard the word ‘wave' thrown around in the news to signify what stage of the pandemic we're in. But while the presence of waves are a necessity for change, they only represent a temporary phase. I am not defined by illnesses, rejections, or hardships, and neither are you. Together, we can link literary arms to help one another cope with, and get through, this wave. As our favourite animated blue fish says, let's just keep swimming together.

Once upon a time, there was a little boy, with no name, no color and no place to live. They say he lived in the sunflowers as there was his favorite place, but the thing is that he couldn't, actually see them, he was blind. The only color he had on him, was the black of his beautiful curly hair. Fed up of not being able to see the beauty around him, the little boy went to the wisest man in his village, he was known as “THE EBONY GUARDIAN”, he lived in a small, humble house just out of the beautiful sunflowers field, he was known to be the darkest man of his village and therefore, the wisest. As in the whole village, black was considered a sign of nobility and wisdom. “Master”, said the little boy, in sign of respect. “May I ask you something?” “sure, go ahead little boy!” said the man, looking at him. “do you know who I am, or where I come from or why I have no color at all?! I wish I could have a color just for me” said the boy looking sad and frustrated at the master. “I don't know what color you are or what is your name or where your place on the Earth is, but I can show you a place in this word where all the colors live together in the light that you can see and in the dark that hides everything”. saying that the master led the boy to the most beautiful place he'd ever seen, full of butterflies and flowers. The boy looked at the master curious and said: well, these are all the colors the world can be? Where's mine then? What color should I be? Do they speak any language that I could learn or am I a stranger even here? Whispered the boy so disappointed. “shhh! Whispered the master smiling at the boy, “watch”, added him pointing at the sky. The boy couldn't see anything so far. “White as the light before to show up its shades, black as the night where all the colors rest, until a new day comes and the rainbow lives again”. As soon as the master pronounced those words a wonderful rainbow stood up in the sky, with incredible, brilliant colors. Those colored lights hit the boy who had finally found what color he wanted to be, not just one but all the colors of the light, all the magic of a rainbow. “what's your color then?” asked the master “All the colors of the light!” exclaimed happily the boy. “And what's your name?” “Rainbow!” “And, finally: where do you come from?” “I come from the light that spreads in the world all the wonderful colors of the rainbow! The boy eventually, had found his colors, a name and his place, he always kept on the top of his head the black where the colors were hidden. And while the world goes on, fighting to decide who sparkles more than everyone, somewhere in a nowhere there always will be a rainbow to show the light with its colors and a dark, quite night to let them rest until tomorrow.

It seems as if I've begun again in the confinement of my bedroom. Shed my skin anew somehow. I tell others, "I do my best thinking when I work with a group!" But that always felt like an excuse to be heard. And to share my revelations with an audience. The trouble with isolation is that it allows you to think. Unpolluted. Without influence. With no audience. Suddenly things you knew to be truthful are not. And things you claimed to know are simply theory. And the person you understand like the back of your hand simply changes. I could tell others, "I do my best thinking when im alone!" But that would feel like an excuse to deconstruct myself. And to open the crevices of my mind and rearrange them to satisfaction. The trouble with isolation is that it is warm and dark. Brimming with damp. And ideas that seemed to be confined to small germs in small circular dishes. Just grow. and grow. and grow. Would it be so far off to say, "you were a completely different person when this started." I thought I knew myself. Knew what I liked. Knew what I loved. Alas, I was wrong. Polluted, with influence from an audience. I found myself questioning systems. Dissecting societal boundaries. Venturing past my knowledge of what it meant to be free from the binary. Past consciousness and decolonization. Confinement has possibly been one of the most freeing experiences of my life. That is not to say that I don't miss the wonders of the world. The beauty of comparison and admiration. Of envy and social calling. Of creation and of critique. It is simply to say self reflection true self reflection comes to me when I am alone. Identity blossoms and twists to face the sun. With nothing but time on my hands due to an everlasting quarantine. I water that garden unknowingly. I grow into someone else completely. I think that i grow into me. I think that I shed my skin anew. I think I've begun again. I think. I've done a lot of thinking.

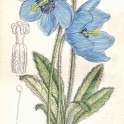

Gasping for air, I woke up. There was a blanket in my hands — grasped tightly like a shield to protect me from the cold air. I stretched my legs and my arms, trying to shake away the grogginess from my sleep. I sat up anxiously. I checked my calendar. My phone read “No events planned.” It was just a regular Saturday morning. When I was a child, I often played in my backyard. I took many pictures of birds and butterflies and bees that had come to visit, zooming in to see the spectacular design of such creations. I looked for the tops of the trees that seemed to never stop growing. I smelled the beautiful roses my mother had planted, along with the daisies that neighbored them. Often, I laminated the leaves and the petals and anything that caught my eye. Laminating the beauty around me was my safe zone. I had found a way to keep something to myself, a permanent design to the things I cherished. My favorite was a Himalayan Blue Poppy that sprouted out of nowhere in my backyard. It was unique to me, full of idiosyncrasies unlike the others. The whistling wind brushed through my hair as I flew my kite in the spring breeze. The flourishing flames warmed me as I sat by the fire on summer nights. The gritty ground sifted in my hands as I tried to search for earthworms and roly-polies in the chilly autumn. And the restless rain poured down on me as I danced in the showers of winter. I often gazed at the beautiful sky, marveling in awe of its different colors: a vast light blue to splashes of purple, red, orange, and yellow to a black and blue sky, splattered with dots of white — the universe calling to be searched and understood. I was young, full of curiosity and admiration for this complex world around me. I wanted to learn everything there was to learn about the galaxy I lived in and the galaxies beyond our grasp. That same world, however, also destroyed my love for it. Soon enough, that boy disappeared. It was September of 2015. My priority immediately shifted from my passions, my education towards my friends and their validation. I got stuck in a never-ending cycle of disappointment, hardships, and temporary happiness. I had stopped doing my homework. Throughout high school, I spent my life trying to please friends that never reciprocated the effort I put in. Yet, I stayed, having found purpose in pleasing those around me. I served them. I fulfilled their every need only to be tossed aside when a better opportunity arises, and when they were done with me, I moved on to the next group of friends that went on to use me. I waited at their beck-and-call if they needed anything. I did this for four years. Walking down the ramp with my diploma, I wondered why I put myself through such hardship. I wasn't proud of anything I did in high school. I had nothing to be proud of. I didn't earn any achievements. I did nothing to receive anything, but in that, I lost everything. It's Saturday morning. I looked around the house to find something to do. I stood up, searching my house to find anything to occupy me. It had been two months since we graduated and I walked around, trying to look for a purpose. I felt like an empty vessel — a spirit, dead inside a physical embodiment of lost passion. “Tristan!” My mother called me to the living room. I looked out at the sea of crafts I made when I was a child. Paper plates wrapped in aluminum foil to simulate UFO's were displayed along with different colored kites in all sorts of shapes and sizes. I walked through the living room lost in the huge mess that my mother had created. “Mom, why did you take everything out? My friends might come over anytime. This is embarrassing.” “I'm cleaning the garage! I was just wondering if you wanted to keep anything.” “Just throw them out. They're just pieces of garbage anyway.” My mother mumbled to herself, exclaiming what a waste it was. I helped her bag things up from the tinfoil UFO's to the kites that I flew one spring. Paper planes and printed photos of birds and bees and butterflies were discarded one by one into the black trash bag that sucked in my childhood. As I threw each picture into the bag, my heart felt heavier and heavier, but I still managed to throw it all out. Then a particular box that my mother had in her hands caught my eye. “Mom, can I see that box real quick?” In front of me was a large box, gray in appearance yet tinted with a sky blue hue underneath the dust that had covered it. Inside it were the laminations I had from childhood. They filled the box, labeled in their species and the date I had found them. Nostalgic, I rummaged through the box trying to find a specific one. In what was over a span of five minutes, I searched for a specific lamination that felt like five decades. One after the other, I discarded the leaves and the petals that covered my treasure. Then I saw it. I found the lamination of the Himalayan Blue Poppy that I had been searching for all this time.

It was still the beginning of the academic year and my friends wanted us to study together. One of us offered to host us at his place, as he had a black board that we could use to do mathematics. I wasn't a good student, I hadn't been one for a very long time, but I tried to pass, so I welcomed the idea and decided to be apart of it. It didn't last for very long. I don't think I have ever known why we only had a few sessions. But we really worked, I mean, they really worked as most of the time I didn't do much. For some reason, my interest in school had grown weak over the year. I often felt like I was in a cage where I wasn't allowed to express myself and do my best. I was actually repeating the class, the four of us, Thiam, Yannick, Gabin, who was hosting us, and me where all in the same class the previous year. One day, we were working on some maths exercises. A student from a literary class of our high school came to us and asked to help him solve a few exercises. We hadn't covered the chapter yet, but we had instructions in the book, so we proceeded to help him. I was sitting and watching my friends doing the work most of the time. But then came a problem that we didn't know how to solve. That caught my attention. No one had a clue of what method or formula we could use to solve it. But looking at it, I thought I might be able to figure out the answer. I could remember that I attempted the previous year to do the same unsuccessfully. But I thought that maybe this time I could. I was hungry so I went out to the shop nearby, bought some biscuits and went back. I sat back and looking at the problem on the board, I thought deeply. As I got close to finding the answer, I stood up and went towards the board. I found it and wrote it on the board. What I did after was pretty unexpected. I told my friend, “This is the answer that was asked. Now how do we get here from the given data?”. Gabin protested, “Is that really the kind of answer that was asked?!” Thiam initially thought it was but they had to argue for a little while until they agreed. I let them talk among themselves, and when they were done, I asked again how we could get there. Thiam asked me, “But how did you come up with that answer?” and I just replied, “I thought about it.” I knew I could do things most people could not, but even though back then they called me Genius, they didn't really know what I had in my toolbox. We had to wait for a while before Thiam finally found in the book the method we needed to use to solve the problem. He applied it and to their great surprise, he found the same answer as what I had written on the board. I didn't get praised of it, they were shocked! Thiam asked, “How did you manage to get that answer?!” I told him again that I had thought about it and added that I could do this kind of things. He started suggesting that I should be a very “spiritual” person, that I had done something mystical when I went out to get the biscuits. I didn't like it. I never liked to hear my classmates attributing what they didn't understand to spiritual phenomenon. In the past I would object whenever some of them would say that the scientists who discovered the laws of science and established formulae were involved in spiritual activities. At times I would tell them that I could do the same and didn't need to leave my body. But they wouldn't believe me. How could they? I was an average student, and to many them, it meant that I was better than them. That day my classmates actually witnessed my ability, but they were still not willing to just let me tell them how I did that exploit. The day after, we were walking home, and someone brought up what had happened the previous day. Thiam, who is a critical thinker, expressed his intrigue saying, “I went home asking myself -How did this guy do it? -, and I was struggling to sleep.” I started telling them that what I had done was not, extraordinary but he objected that it was mind blowing. He asked Gabin to confirm, which he did. I told them that it was normal, that some people had abilities that allowed them to understand science at a deeper level, but they weren't many. I had believed for a long time that they were others like me, and I faced so many challenges because we were scarce and as a result, people were not used to dealing with the way we function and witnessing what we could do. That day I felt so different and alone! I knew my friends and what they could do as human beings. But there was a part of me that they didn't know at all, one that caused them to look at me as if I was an alien who just landed from a spaceship, when they witnessed it. I thought that if more people knew about our existence, such things wouldn't happen to us. That day, like many other days, I felt like letting everyone know. I felt like shouting to the world “We exist!”.

I consider it an ordeal to travel in Africa. My parents traveled a lot when I was younger and I have always wanted to travel too. The way they talked about living in Northern Nigeria, it feels like a different world from now. They never felt like strangers whenever they left home, but Africa is changing. It's meant to be the height of experiences; for young people to pack a bag and travel to see the continent but present day Africa could be as hostile as it is beautiful. Being a stranger is not just about changing GPS location, it's about being where you are not expected to be. I am Nigerian and I am skinny. One would think identity and body size are just what they are but along with identity comes the burden of stereotypes. After a few months of arriving South Africa from Nigeria, I visited an Indian Doctor in Hatfield, Pretoria. The first thing he said was "You are Nigerian, so you gonna pay me with drugs? Ahh! I am joking!" Very inconvenient joke I must say, but that was my reward for being Nigerian in South Africa. In moments like those you almost feel as if you are not welcome, that you are a stranger. South Africa is a good place but when it comes to making jokes, it sucks some times. Some locals tell you how they actually think about you -probably something bad- and then they add that it's just a joke. What better way to peddle stereotypes than to make jokes about them? Now every Nigerian who leaves home is a drug peddler? The moment we step out of our borders we are labelled. I have also heard that Indians are rapists and drug abusers too. Should I have said so to that doctor and probably added "I am joking?" The student medical aid is compulsory for all foreign students including Nigerians who are just a little different from South Africans. The medical aid is crap from what I hear and I am sure they also know I am Nigerian and think "probably he is a drug peddler." What happens when I need to use this aid? What if someone does not attend to me just because they think I am a criminal. The day I visited the GP at Hatfield, I had to pay the Indian Doctor with cash that I don't have and he told me it might take another century to get my claim back. It actually took a century to get the claims department and they never paid. *sigh* That day after telling me what was wrong with me, the Doctor gave me some drugs and warned that I must eat before taking the drugs. He said "You look skinny, either because you don't have food or you are just skinny." After worrying about my citizenship, now I had to worry about my body size. There are fat humans, average sized humans, skinny humans and so on and so forth. How long would it take for us to accept these differences? The whole idea of racism and apartheid thrived on the idea that skin colour is a definitive element of your humanity. Skin colour, body type, hair or any other body feature are things no one chooses. Yet a lot of us are made to feel like we don't fit in, just because of these things. People avoid you for as little as the fact that how you look or talk or walk is strange or new to them. I am skinny not by a fault of my own, my body structure is far from perfect for those who have seen me. I limp slightly, and it's not from an accident. I was born with a birthmark on my forehead and for years I felt different. There are so many funny things that are not "right" about my looks but everyone has their own weird features. If you looked around you, there are at least a hundred people who don't look exactly like you just because they eat different or live in a different environment. But these people are just as human as you are. Holding a Nigerian passport or walking with a limp doesn't make one human better than another. The value of life is one and the same all over the world. Being a stranger in Africa stems from the dying culture of inclusiveness, community and hospitality that Africans used to be known for. There is a hate culture eating deep into the fabric of our lives, we have been hunted, haunted and broken by strangers. Understandably, suspicion and fear becomes a defence but must we lose the beauty of Africa to fear and hate? We need to embrace universal citizenship, to travel, to love, to eat with and walk with people who seem different from us. There's no need for us to be strangers in our own world.