My Aunt's Diary

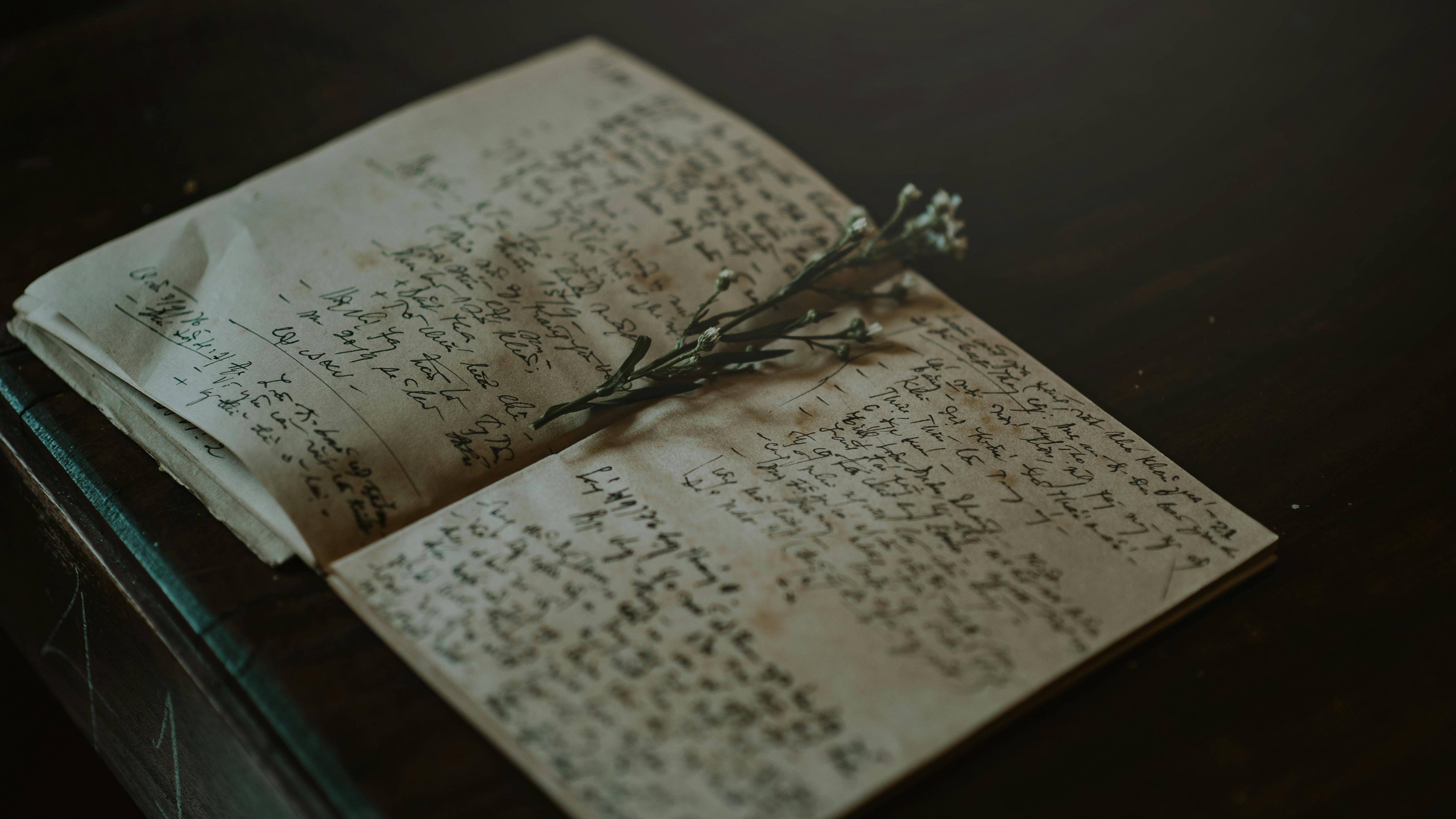

“An old man's memories are his best companions.” We'll get to that later… It's been a few years since I've visited my cousins. There's almost a generation gap between me and my father's side of the family—while I belong to Gen Z, they go back to Gen X or what we modern folks like to call the classical period. When we picture the '80s and '90s, names like Michael Jackson and Muhammad Ali immediately peaks in our mind. As my father used to say, "Ah, the good old days—when we weren't good, but life was." According to our pioneers, people were happier than now. Indeed, we like to think we're progressive while they are stuck in the past. Certainly, we are more liberal and materialistic. But, they are more culturally pure, connected more to the traditions and norms. Senior citizens always think of it as a curse. But isn't that the irony of the journey? The further we progress to modern life, the harder it becomes to forget the past. Cousins are supposed to be like two peas in a pod, but ours split somewhere along the family tree. It's like mixing a smartphone with a typewriter—both useful but from different worlds. My mom's side is another story entirely, one that I, as a male writer, won't complicate here. It's my aunt's third death anniversary. My cousins organize prayers in her memory each year. Last time, I had a valid excuse to miss it. Being an introvert, I often retreat to the guest bedroom at their house. There's an old radio there that I love. My uncle was a strict and conservative muslim. Once, he forbade his children from bringing a television into the house. Since then, no television had ever made its way through that door. Just as I was about to turn on the radio, I remembered the occasion. Listening to music at a death anniversary would be downright criminal. Instead, I reached for a book. That's when I noticed a dusty, worn-out book sitting on the shelf. I wiped it clean with a scarf, only to realize—it was my late aunt's diary. The very same one she used to give to every guest who visited her. I had only visited her house three times. The first was when I was too young to remember much. It was a family gathering. One of my cousins had toy cars, but he didn't like sharing. To keep me entertained, my aunt brought out an old baby walker. But soon, my younger brother—just learning to walk—became the center of attention. The second time was during a family vacation. We visited Dhaka University, the Martyrs' Monument, and the National Museum. The museum fascinated me. My mother often told stories about February 21st, 1952—the Language Movement. Her uncle, a police officer, was martyred that day for refusing to fire at students. Inside the museum, I saw a bloodstained shirt of a language martyr. The third visit was an emotional one—it was during the final days of my father. He had been diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. We were too young to react according to the situation. I was in seventh grade, and my younger brother and I treated the visit as if it were just another vacation, unaware that our family was on the brink of a crisis. We never stopped to wonder—what would happen to us if my father, the sole breadwinner of our household, was gone? My father was the all doer of the family. He frequently used to say to me alone, "From now on, you have to take responsibility." But how could I? I was just a child. A month later, he passed away. All of this happened 10 or 20 years ago. If I hadn't watched Inside Out, I'd probably still be wondering how my mind managed to store all these memories. Thanks to my brain's leader, Joy, for keeping them safe. Good job—hats off! Oh wait… do emotions even wear hats? Now, why have I told you these stories? Because, those stories I have just told, were there in my aunt's diary, written by us. It felt as if the past had come alive. It was almost as if I could see my father right in front of me with my own eyes. The words in the diary were coming to life; they were echoes of the moments we lived. Suddenly, I was seeing myself—standing with my father in front of Dhaka University Snacks (DUS). The university roads stretched before us, only a few couples strolling by, a band of young musicians rehearsing at TSC. Those roads weren't perfect—holes everywhere—but the rain had filled them, creating puddles that mirrored the sky. In those reflections, pedestrians can see flashes of their future—the future I'm now walking in. Now, as I walk through my campus, I remember those beautiful moments and whisper the same words my father used to say: "Ah, the good old days..." I hope now you understand why keeping memories alive is so important—why we need something tangible to hold on to, to keep the touch of our loved ones from fading away. As American actress Mae West once said, "Keep a diary, and someday it'll keep you."